Life, Novels

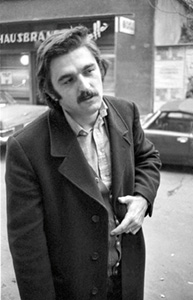

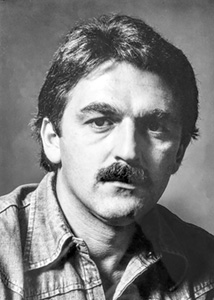

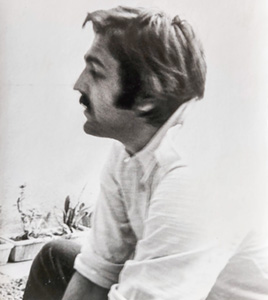

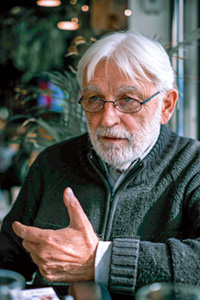

DRAGO KEKANOVIĆ, SERBIAN WRITER WITH A ZAGREB ADDRESS

Leaving Your Homeland Is in Vain

I had a homeland, sure I did. Not any longer. The less real reasons to return to it, the more often it will approach you. Finally, the graves will summon you. Yes, I believe in spiritual aristocracy from the first written sentence. I think that there is no good literature without the awareness of Tradition, which also implies Language. Everything else is a triumph of vulgarity and ignorance. Following trends is fatal, in every aspect. Literature has always been bigger than the world it is realized in. A strong and accurate word survives and lasts. There is no crisis for singing and narrating; as long as language is a fathomless secret, poets and narrators will best testify about the end of the world

By: Branislav Matić

Photo: Mileta Aćimović Ivkov and Private Archive

Aware of his isolation, he knows it is a cross and measure. Already at the farm in his birthplace of Bratuljevci under Papuk in Slavonija, he realized that loneliness is more beneficial than any noise and uproar. His decision to stay in Zagreb, among the cast out of the Constitution, the surrounded, disenfranchised, satanized, is also a kind of isolation.

Aware of his isolation, he knows it is a cross and measure. Already at the farm in his birthplace of Bratuljevci under Papuk in Slavonija, he realized that loneliness is more beneficial than any noise and uproar. His decision to stay in Zagreb, among the cast out of the Constitution, the surrounded, disenfranchised, satanized, is also a kind of isolation.

He believes in the power of literature and words which will outlive the world. He understood the light of forests and mechanics of the night as a very young man. He sees that mediocrity and vulgarity are offensive, they are grabbing for glory and recognitions, and although they most often snatch them, that does not make him waver. He learned that patience is more valuable than gold and that everything will, sooner or later, come to the right place.

Drago Kekanović (1947) in National Review.

Family. It is very likely that all seven Kekanović collectives rushed together from one slavery to another and hid under the auspices of Mary Therese at the end of the eighteenth century, in the years of great turmoil among stars and nations. Young Tito’s pioneer, who searched for his origin, could not be satisfied with vague answers that we arrived to Bratulje somewhere from the sea and from the south. But, where from?! From the Montenegrin coast or Dalmatian hinterland, no one remembered anymore. No one also remembered or knew why they were late and why they lost an entire century compared to other inhabitants of the Slavonian village under Papuk,  at the very border of the Military Borderline. The only logical conclusion for a young pioneer, then already influenced by adventure novels, was that the Kekanovićs were martolos, armed servants, Turkish paramilitary, as we would say today, who just waited for the right moment to change into the uniform of Austro-Hungarian frontiersmen. However, such a conclusion was also shaky. During the years of his growing up, credible witnesses died one by one, and funerals took away those wonderful, bony and sharp-witted, tall (none of them was less than two meters tall) old men, whose memory (usually) refused to summon the Turkish times of their parents and ancestors, but rather remained in the years of their youth, the days when they walked the streets of Timisoara, splashed with kisses of smiling, dark-tanned Wallachian girls. Be as it may, the young pioneer (the world was waiting for him!) gave up searching for his origins.

at the very border of the Military Borderline. The only logical conclusion for a young pioneer, then already influenced by adventure novels, was that the Kekanovićs were martolos, armed servants, Turkish paramilitary, as we would say today, who just waited for the right moment to change into the uniform of Austro-Hungarian frontiersmen. However, such a conclusion was also shaky. During the years of his growing up, credible witnesses died one by one, and funerals took away those wonderful, bony and sharp-witted, tall (none of them was less than two meters tall) old men, whose memory (usually) refused to summon the Turkish times of their parents and ancestors, but rather remained in the years of their youth, the days when they walked the streets of Timisoara, splashed with kisses of smiling, dark-tanned Wallachian girls. Be as it may, the young pioneer (the world was waiting for him!) gave up searching for his origins.

Even reputable professor Ljudevit Jonke, undisputed authority of (then) Croato-Serbian linguistics, did not find a way to explain his student (which was, apparently, his favorite pastime) the basis, phonetic root and meaning of those few vocals and consonants we respond to. Confronted with the family name Kekanović, the professor was in a dilemma as well. Yes, there are those with Kikan and Kokan, but this was the first time he heard about Kekan. My explanation that only seven houses in Bratulje, there under Papuk, are carrying that surname, did not help the professor to decide. Because there were two possibilities. The first suggested that the root of the surname originates from an extinct kind of bird, keja, who used to live in the narrow stripe between the land and the sea in the Neretva valley; loud and noisy colorful birds similar to inland garrulus. The second possibility also leads to the sea, to the areas in which every old woman is a Keka, especially those which fate made, in the absence of male leaders, heads of collectives, families, clans, leading them towards tomorrow, towards staying alive and survival.

Even reputable professor Ljudevit Jonke, undisputed authority of (then) Croato-Serbian linguistics, did not find a way to explain his student (which was, apparently, his favorite pastime) the basis, phonetic root and meaning of those few vocals and consonants we respond to. Confronted with the family name Kekanović, the professor was in a dilemma as well. Yes, there are those with Kikan and Kokan, but this was the first time he heard about Kekan. My explanation that only seven houses in Bratulje, there under Papuk, are carrying that surname, did not help the professor to decide. Because there were two possibilities. The first suggested that the root of the surname originates from an extinct kind of bird, keja, who used to live in the narrow stripe between the land and the sea in the Neretva valley; loud and noisy colorful birds similar to inland garrulus. The second possibility also leads to the sea, to the areas in which every old woman is a Keka, especially those which fate made, in the absence of male leaders, heads of collectives, families, clans, leading them towards tomorrow, towards staying alive and survival.

As for my mother’s Vučković family, things were much clearer. They came to Slavonija from Bosnia. Central, I suppose. Certainly, inhabited by wolves. The Vučković family did not care much about where they came from either. They forgot, so what. As if anyone cared. They did not. Who would still think about origins and the past? When you have to spend a winter in the gloomy deep river valley between hills, which the sun barely touches through the arches of thick vegetation, when you cannot make one step without stepping into flowing water or slushy mud. And it was the same every autumn, until the summer comes. In summers, though, it was much more comfortable and enjoyable. You could run barefoot and leave a cloud of dust behind. And during summer downpours, there was no one happier than your pioneer. The soggy soil yielded to hands, so he made noisy cannons out of mud, competing with his peers in the valley in noisiness and loudness. Oh, how it blasted!

Homeland. You leave the homeland, but in vain. Never permanently. The autumn of 1991, however, tried to cut me off from my homeland forever. When I stumbled upon the remains of the destruction of my homeland library on the muddy way to my house of birth, on a road cut into ravines, arched by bushes. A passionate collector of rare books from antique shops mostly in Zagreb, as well as Belgrade, Ljubljana, Vienna, books purchased in any city I would visit for any reason, stopped shocked, he could barely hit the brake, before a surrealistic scene: the muddy road, a section of the somewhat reliable motorway, cut among the slopes with unrestrained vegetation, was covered with scattered books. Only someone who wanted to get rid of a loaded, yet redundant and useless burden, because they made a good estimate that they would earn more money from a few oak tree trunks than from selling those stupid books in bulk to the Sanitation Department, could do it. Since that day, I just pass by antique shops. But you cannot go pass by your

Homeland. You leave the homeland, but in vain. Never permanently. The autumn of 1991, however, tried to cut me off from my homeland forever. When I stumbled upon the remains of the destruction of my homeland library on the muddy way to my house of birth, on a road cut into ravines, arched by bushes. A passionate collector of rare books from antique shops mostly in Zagreb, as well as Belgrade, Ljubljana, Vienna, books purchased in any city I would visit for any reason, stopped shocked, he could barely hit the brake, before a surrealistic scene: the muddy road, a section of the somewhat reliable motorway, cut among the slopes with unrestrained vegetation, was covered with scattered books. Only someone who wanted to get rid of a loaded, yet redundant and useless burden, because they made a good estimate that they would earn more money from a few oak tree trunks than from selling those stupid books in bulk to the Sanitation Department, could do it. Since that day, I just pass by antique shops. But you cannot go pass by your  homeland or denounce it. The less reasons you have got to return to it, the more often it will approach you. Finally, the graves will summon you. As well as the branches of the old sort of apples in the abandoned apple orchard, a plum in the former plum orchard, the old Lazankinja pear, with dry branches and at the end of their strength, still powerful, however, to taste a fruit you cannot find in any supermarket.

homeland or denounce it. The less reasons you have got to return to it, the more often it will approach you. Finally, the graves will summon you. As well as the branches of the old sort of apples in the abandoned apple orchard, a plum in the former plum orchard, the old Lazankinja pear, with dry branches and at the end of their strength, still powerful, however, to taste a fruit you cannot find in any supermarket.

I had, of course, what is called homeland, which implies sunny mornings when you don’t know what to do with your outpouring strength, so you just rush around, run down dewy paths through fields, until you fall from tiredness and until your mother calls you for breakfast, and chores, after breakfast of course. Today, you don’t even dare think of the evening sky, sunsets and dreams at dusk, the blue dome covered with stars while you are lying in the wheat. I had all that, I don’t have it anymore.

Paradoxically or not, however, already with my early departing from my birth home, separation from the morning rituals on a, to a certain degree preserved landowner’s estate and farm in the 1950s, to not so far Požega, and then to Osijek, the melancholic premonition of eternal exile and lack of homeland, eradication, a kind of damnation, was starting to grow, and just just piling up by reading Rilke and Kafka, Heidegger and especially Crnjanski. That, less a feeling and more a premonition of an irreplaceable loss (of homeland) cast like a shadow over all the pages I was only about to write. But that is a different story.

Zagreb. Zagreb, the one from the late 1960s and early 1970s formatted me, without any doubt, both spiritually (I am not ashamed of notorious exhausted phrases) and intellectually. To the extent, of course, any city, any intellectual environment, can influence the mental and spiritual development of a young man. The city, environment, agora, polis, as you like, with every published short story, note, theatrical or film criticism, essay and lyrical inscription, drew my profile into its literary map. I was accepted, as it is said, among people whose opinion I cared about. Awarded as well. What more could I want?! However, speaking in sports language: Zagreb was not my first choice. Most of my peers studied in Belgrade. However, the diploma of the “Ruđer Bošković” school of architecture and civil engineering was not recognized as a valid document for enrolling in any of the social sciences faculties in Belgrade. All my pleas and assurances that I am ready to pass tests in all subjects I did not have in technical school did not yield any result. Thus, in the tormenting and difficult transformation between architect and civil engineer and my literary ambitions to perceive the world from a different side, I found myself on a turning point which, instead of to the East, turned me towards the West. As far as I remember, I passed all the tests in Zagreb without much effort. And so, my second choice became my first.

Honestly speaking, my arrival to Zagreb was not a traumatic experience. Because Zagreb and I have already been on first name basis, so to say. In order to understand what I am going to talk about now, I have to remind you that the communist-Michurin agenda was in its climax those years, and that Slavonija, including the Požega valley, was flourishing. Yes, my grandfather Petar, former member of Privrednik (Businessman), former landowner and supporter of the Pribićević-Radić coalition, a kulak who later spent time in Lepoglava and Nova Gradiška, even dug the “Fraternity-Unity” Highway, was suddenly rehabilitated. And my grandfather needed only those two or three years of freedom to win first awards and golden plaques with products and exhibits from his estate reduced by confiscation and agrarian reform (with the wholehearted support of my father Lazar, resigned party member, and mother Anka Vučković, passionate member of SKOJ) at fruit growing and viticulture, wine and brandy fairs. Thus, my good Petar qualified in Požega for the republic exhibition at the Zagreb Fair in Savska Street. Neither Anka nor Lazar wanted to leave (the somewhat senile, of course) grandfather without escort, so they assigned me the great responsibility to watch the old man. They also thought it would be good for me to see Zagreb. Oh, yes, with my grandfather and his buddies, I partied in Zagreb kafanas, waiting for them to leave and to offer grandfather my shoulder and arm to take him to our room in “Lovački rog” (“Hunter’s Horn”) in Ilica. For five years, my grandfather and I brought golden medals and plaques ornamented with copper

Honestly speaking, my arrival to Zagreb was not a traumatic experience. Because Zagreb and I have already been on first name basis, so to say. In order to understand what I am going to talk about now, I have to remind you that the communist-Michurin agenda was in its climax those years, and that Slavonija, including the Požega valley, was flourishing. Yes, my grandfather Petar, former member of Privrednik (Businessman), former landowner and supporter of the Pribićević-Radić coalition, a kulak who later spent time in Lepoglava and Nova Gradiška, even dug the “Fraternity-Unity” Highway, was suddenly rehabilitated. And my grandfather needed only those two or three years of freedom to win first awards and golden plaques with products and exhibits from his estate reduced by confiscation and agrarian reform (with the wholehearted support of my father Lazar, resigned party member, and mother Anka Vučković, passionate member of SKOJ) at fruit growing and viticulture, wine and brandy fairs. Thus, my good Petar qualified in Požega for the republic exhibition at the Zagreb Fair in Savska Street. Neither Anka nor Lazar wanted to leave (the somewhat senile, of course) grandfather without escort, so they assigned me the great responsibility to watch the old man. They also thought it would be good for me to see Zagreb. Oh, yes, with my grandfather and his buddies, I partied in Zagreb kafanas, waiting for them to leave and to offer grandfather my shoulder and arm to take him to our room in “Lovački rog” (“Hunter’s Horn”) in Ilica. For five years, my grandfather and I brought golden medals and plaques ornamented with copper  engraving from the Zagreb Fair to our muddy Bratulje. Then, somehow, I don’t know how, it stopped, and everyone was saying that there was a strong turn in the agrarian policy. I could only remember the breakfasts in “Lovački rog”, with coffee with milk, two sunny side up eggs and a warm kaiser roll, which melts in the mouth.

engraving from the Zagreb Fair to our muddy Bratulje. Then, somehow, I don’t know how, it stopped, and everyone was saying that there was a strong turn in the agrarian policy. I could only remember the breakfasts in “Lovački rog”, with coffee with milk, two sunny side up eggs and a warm kaiser roll, which melts in the mouth.

In the early nineties, after another breakdown and turn, actually a coup, I often encountered the question: how is it possible that you, a Serb and Serbian writer, live and write in Zagreb?! My acquaintances often asked me that question, mostly those with good intentions, who advised me to move as soon as possible. My answer that I will move when I want to, maybe never, never pleased them. At the time, I was member of the phantom association of Free Writers of Yugoslavia, which was soon ground-up by the grindstone of events and scattered back to their republic compartments. Some of those writers achieved, in local proportions, enviable international literary careers, some talked me into joining them, but I was not attracted to the fate of stateless ones; I could not imagine a greater apostasy than a step into complete uncertainty of joining those expelled from the Constitution, decapitated, thrown out of new historical streams, pushed aside and deprived of any rights to the status of minority, and exposed to a horrible media satanization. So, I remained in Zagreb. Among my people.

Personal Map of the City. I have those special places. Who doesn’t?! When the homeland soil slips away beneath your feet, you find such special places, energy fields, or whatever they are, more with your instinct than with reason, places where you collect yourself in sensitive moments most quickly, and such moments do not only include inevitable losses in life, but also moments of exaltation with a new verse or sentence. They are losses as well, since you will never again summon that verse or that sentence, if it slips away before you write it down. I don’t know, perhaps such places choose us, and there we satisfy in the best way the purpose of our existence in cosmic infinity. While in Požega, I always went out to Orljava in such moments, perhaps hoping that a school of crabs will crawl out before me from my Bratuljevo mountain Crab Creek; not a single one ever crawled out. While in Osijek, I also went to the water and sat for a long time next to the Drava; already without hope; or, I’m lying, perhaps with a small hope that the water would take me to the confluence into the Danube and further. With Zagreb is a whole different story. Popovski Vrt, Ribnjak (Fishpond) Park and the botanical garden next to the Kaptol walls bound me as soon as I stepped into the covered bottom of a former fishpond (where carp, pikeperch and trout were bred for the needs of the bishopric palace). History says that the age of industrialization and its accelerating urbanization (and when wasn’t it accelerated?) demolished the Kaptol middle ages, walls and remaining walls, the fishpond was dried, so it became a perfect place for planting saplings which missionaries of the Catholic Church brought from all continents. I don’t know how the Ribnjak Park became my secret place, the place in which prose chapters are written by themselves; the very thought of sitting on a bench in a former water of transience (of what?!), if it doesn’t sound too pathetic, with sycamore trees murmuring or a very tall North American sequoia swinging above my head, made me completely peaceful and collected. Of course, that has disappeared as well. Year after year, summer storms have been hitting the park, tearing down the highest, seemingly healthy trees. The Ribnjak from the past and the one now cannot be compared. But I myself cannot be compared either.

Personal Map of the City. I have those special places. Who doesn’t?! When the homeland soil slips away beneath your feet, you find such special places, energy fields, or whatever they are, more with your instinct than with reason, places where you collect yourself in sensitive moments most quickly, and such moments do not only include inevitable losses in life, but also moments of exaltation with a new verse or sentence. They are losses as well, since you will never again summon that verse or that sentence, if it slips away before you write it down. I don’t know, perhaps such places choose us, and there we satisfy in the best way the purpose of our existence in cosmic infinity. While in Požega, I always went out to Orljava in such moments, perhaps hoping that a school of crabs will crawl out before me from my Bratuljevo mountain Crab Creek; not a single one ever crawled out. While in Osijek, I also went to the water and sat for a long time next to the Drava; already without hope; or, I’m lying, perhaps with a small hope that the water would take me to the confluence into the Danube and further. With Zagreb is a whole different story. Popovski Vrt, Ribnjak (Fishpond) Park and the botanical garden next to the Kaptol walls bound me as soon as I stepped into the covered bottom of a former fishpond (where carp, pikeperch and trout were bred for the needs of the bishopric palace). History says that the age of industrialization and its accelerating urbanization (and when wasn’t it accelerated?) demolished the Kaptol middle ages, walls and remaining walls, the fishpond was dried, so it became a perfect place for planting saplings which missionaries of the Catholic Church brought from all continents. I don’t know how the Ribnjak Park became my secret place, the place in which prose chapters are written by themselves; the very thought of sitting on a bench in a former water of transience (of what?!), if it doesn’t sound too pathetic, with sycamore trees murmuring or a very tall North American sequoia swinging above my head, made me completely peaceful and collected. Of course, that has disappeared as well. Year after year, summer storms have been hitting the park, tearing down the highest, seemingly healthy trees. The Ribnjak from the past and the one now cannot be compared. But I myself cannot be compared either.

Under a Black Shadow. I see the crisis so much that I am investing all my efforts not to see it. I am fooling myself, of course. Clearly in vain. A black shadow has passed over us here, however, not only in Zagreb and Krajina, but in all areas we have been living for centuries, which overshadowed and erased everything we knew up to then and everything we believed in. It is a (Tesla, help!) an experience (is it the right word, I’m not sure it is) which is universal, impossible to retell, not only to others but also to oneself. It is implied that others, those who were not in our shoes, cannot understand us. We are an overshadowed nation here, and no one should bet a cent on us on historical betting sites. Whatever direction we take, there will be less and less of us, and we should not delude ourselves with false hope that we will return everything we had lost one day (what day?!). What is lost can never be returned anyhow. And if it does return, it is incomplete. In the meantime, the world has completely globalized on global level, now sailing beyond coordinates of the civilizational compass, swaying like a drunken ship, and what happened to that ship was declared a long time ago.

Under a Black Shadow. I see the crisis so much that I am investing all my efforts not to see it. I am fooling myself, of course. Clearly in vain. A black shadow has passed over us here, however, not only in Zagreb and Krajina, but in all areas we have been living for centuries, which overshadowed and erased everything we knew up to then and everything we believed in. It is a (Tesla, help!) an experience (is it the right word, I’m not sure it is) which is universal, impossible to retell, not only to others but also to oneself. It is implied that others, those who were not in our shoes, cannot understand us. We are an overshadowed nation here, and no one should bet a cent on us on historical betting sites. Whatever direction we take, there will be less and less of us, and we should not delude ourselves with false hope that we will return everything we had lost one day (what day?!). What is lost can never be returned anyhow. And if it does return, it is incomplete. In the meantime, the world has completely globalized on global level, now sailing beyond coordinates of the civilizational compass, swaying like a drunken ship, and what happened to that ship was declared a long time ago.

Masters and Students. I have never burdened myself with issues of comparisons and literary influences. I know it is hard to believe, but I never paid too much attention to the public, media echo of my works. I am not one of those who paste newspaper articles and pictures in albums. It is a bad feature, which I would not recommend to a young author. But that is how I am, I don’t know why, and even today I have to push myself to read someone’s review of my work. Complimentary or less inclined, for me it’s all the same. Even if I did start searching for role-models which others discovered in my manuscript, even if I did reach certain answers, I don’t believe they would determine the character of my next sentence. An act of reading is one thing, while encountering the whiteness of paper or light of the screen is a whole different thing. A writer cannot change or move anything. Neither in procedure nor in accepting others. Because there is certainly more unconscious than conscious in the act of writing. For example, in the nineties, a whole bunch of more or less autobiographic, hardly readable works of different genres, crying for being published or adapted for TV, was dumped on me, as editor and dramaturgist. I accepted to read those texts (yes, texts! but I had to feed the family) as a form of punishment. Even today, paradoxically or not, sometimes it seems to me (may Kafka and Bora and Bruno Schultz and Miodrag, and Borges and others, of course, forgive me) that in that illiterateness I cleared up the secrets of formatting a convincing story and sentences belonging to it. Or, as any other offender, I am only consoling myself that the punishment was not in vain and that I gained something from it.

Masters and Students. I have never burdened myself with issues of comparisons and literary influences. I know it is hard to believe, but I never paid too much attention to the public, media echo of my works. I am not one of those who paste newspaper articles and pictures in albums. It is a bad feature, which I would not recommend to a young author. But that is how I am, I don’t know why, and even today I have to push myself to read someone’s review of my work. Complimentary or less inclined, for me it’s all the same. Even if I did start searching for role-models which others discovered in my manuscript, even if I did reach certain answers, I don’t believe they would determine the character of my next sentence. An act of reading is one thing, while encountering the whiteness of paper or light of the screen is a whole different thing. A writer cannot change or move anything. Neither in procedure nor in accepting others. Because there is certainly more unconscious than conscious in the act of writing. For example, in the nineties, a whole bunch of more or less autobiographic, hardly readable works of different genres, crying for being published or adapted for TV, was dumped on me, as editor and dramaturgist. I accepted to read those texts (yes, texts! but I had to feed the family) as a form of punishment. Even today, paradoxically or not, sometimes it seems to me (may Kafka and Bora and Bruno Schultz and Miodrag, and Borges and others, of course, forgive me) that in that illiterateness I cleared up the secrets of formatting a convincing story and sentences belonging to it. Or, as any other offender, I am only consoling myself that the punishment was not in vain and that I gained something from it.

Power of Literature. Literature has always been greater than the world it is realized in. There is no crisis for singing and narration: as long as the language is a fathomless secret, the destruction of the world will be best testified by poets and narrators. Even today, when we are apparently at the edge of the greatest civilizational abyss, I am equally confused by the fact that there are still people who reach out for books. As salvation. Consolation, whatever. What else would they reach out for?!

Power of Literature. Literature has always been greater than the world it is realized in. There is no crisis for singing and narration: as long as the language is a fathomless secret, the destruction of the world will be best testified by poets and narrators. Even today, when we are apparently at the edge of the greatest civilizational abyss, I am equally confused by the fact that there are still people who reach out for books. As salvation. Consolation, whatever. What else would they reach out for?!

My faith in the power of literature is infinite, regardless of the small, even inconsiderable power of its external influence. Sometimes the influence is stronger, sometimes weaker, depending on the social context. For me it’s all the same. A strong and accurate word survives and lasts, regardless of its social, often also politically manipulative distribution towards the reader. Finally, only they, readers, decide about everything (besides experts in literature). And they are not that innocent as it may seem. Sometimes I feel sorry when I see them reading worthless literary garbage, the so-called hits and bestsellers, instead of reading Odyssey or Don Quixote.

Tradition and Faddishness. I believe there is no good literature without the awareness about Tradition, which of course includes Language. Everything else is a triumph of vulgarity and ignorance. Vulgarity is invasive and aggressive, eager for glory and recognition, which it often receives. But then, already the following day, we cannot remember the title that won that prestigious award; libraries are full of forgotten, unread books. Unfounded in Tradition. Faddishness is always fatal, in literature as well.

Tradition and Faddishness. I believe there is no good literature without the awareness about Tradition, which of course includes Language. Everything else is a triumph of vulgarity and ignorance. Vulgarity is invasive and aggressive, eager for glory and recognition, which it often receives. But then, already the following day, we cannot remember the title that won that prestigious award; libraries are full of forgotten, unread books. Unfounded in Tradition. Faddishness is always fatal, in literature as well.

Chivalry Today. Yes, I believe in spiritual aristocracy. Ever since my first written sentence, since my first short story “The First Snow”, published in Požeški List. No one made me or talked me into writing something about a wonderful winter day at the sledging ground in Tekija, a hill above Požega. What made a frozen elementary school student in a cold tenant room leave a short testimony on a piece of paper about the extraordinariness and unrepeatability of the children’s noise and yelling, joy and laughter, is still a secret for me, even in my old days. But that is when it all began.

“Great Minority” and “Dwarf Majority”. I studied, the subject of my studies was Yugoslav literature and languages, I made an effort to read Cankar in Slovenian, Blažo Koneski in Macedonian, and it held me for a few years. I enjoyed it until I realized that language is the only determination of a writer and a literature, and that, already in the late sixties, it will become the main weapon for the disintegration of the world, even my subject of studies as such, built into a plurality, which already implied the splitting and embeddedness of future republic borders as new state entities. I admit, it took me a long time. And I will also never understand the grotesque and cynically imposed relation of the “superior minority” and the “dwarf majority”. What supremacy?! What dwarfs?! When you can clearly see that the allegedly dwarf majority is incomparable larger than the allegedly superior minority. Oh, please! The majority is always larger. And the minority is small, always prone to assimilation, disappearance. How much longer will we be fooling ourselves?

“Great Minority” and “Dwarf Majority”. I studied, the subject of my studies was Yugoslav literature and languages, I made an effort to read Cankar in Slovenian, Blažo Koneski in Macedonian, and it held me for a few years. I enjoyed it until I realized that language is the only determination of a writer and a literature, and that, already in the late sixties, it will become the main weapon for the disintegration of the world, even my subject of studies as such, built into a plurality, which already implied the splitting and embeddedness of future republic borders as new state entities. I admit, it took me a long time. And I will also never understand the grotesque and cynically imposed relation of the “superior minority” and the “dwarf majority”. What supremacy?! What dwarfs?! When you can clearly see that the allegedly dwarf majority is incomparable larger than the allegedly superior minority. Oh, please! The majority is always larger. And the minority is small, always prone to assimilation, disappearance. How much longer will we be fooling ourselves?

Purchasing Time. Unfortunately, I began writing on a typewriter very early. I say unfortunately, because I also made inscriptions, more or less unreadable, in notebooks and on pieces of paper. I cannot boast with that either, like my great role-models, who wrote on restaurant napkins or tram tickets. As for organizing life, it was not easy at all for me to earn enough money as an independent, free artist, to buy a few months of diving into other (my own) worlds of imagination. However, once I do dive, after maniacally vacuum cleaning all the dust from my study, nothing can prevent me from achieving my intention. Yes, I am a last-minute writer. One can notice those big empty spaces, I announce two or three titles every ten years, always waiting for the so-called favorable circumstances. I purchased all my free time by working on television and film scripts. Those were rare moments, but, yes, they do exist. And always in almost sterile residential circumstances: in throwing bales of hay or wheat sheaves, in carrying chaff, I have swallowed enough dust for my entire life.

Lost Heart of the Media. Oh, yes, since I began working in the Television Zagreb Drama Department in 1985, after a decade with a status of free artist, in the romantic Dežmanova Street leading to Ilica and Frankopanska Street in the very heart of the city, the media have transformed to the degree I could not imagine in my worst nightmares. Dežmanova Street was the center of an entire agenda, as people would say today, of both Croatian and Yugoslavian visual art. Just a rough list of directors and scriptwriters, producers and actors I have met would not fit this text. Working on movies is seductive, it occupies you, unlike the loneliness of a working desk, where you fight with your ghosts, it makes you more public, more important and smarter than you really are, so it carried me away a bit as well, enough to not to be able to notice that it was the last stage of intoxication with motion pictures, a swansong of an era. What’s gone is gone, however. And, fortunately, it took me back to my unwritten stories.

Lost Heart of the Media. Oh, yes, since I began working in the Television Zagreb Drama Department in 1985, after a decade with a status of free artist, in the romantic Dežmanova Street leading to Ilica and Frankopanska Street in the very heart of the city, the media have transformed to the degree I could not imagine in my worst nightmares. Dežmanova Street was the center of an entire agenda, as people would say today, of both Croatian and Yugoslavian visual art. Just a rough list of directors and scriptwriters, producers and actors I have met would not fit this text. Working on movies is seductive, it occupies you, unlike the loneliness of a working desk, where you fight with your ghosts, it makes you more public, more important and smarter than you really are, so it carried me away a bit as well, enough to not to be able to notice that it was the last stage of intoxication with motion pictures, a swansong of an era. What’s gone is gone, however. And, fortunately, it took me back to my unwritten stories.

A Weak Hope. The way things are (mid-May 2022) we can only hope for a new order, a New Europe, but the one which will finally be founded on rejected Christian values. For more than a decade, I have been a so-called European citizen, but it is getting clearer to me that I am more and more distant from genuine European values, which I dreamed of in the 1960s and 70s. Budapest, Vienna, Prague were not far away back then. Today, they are much more distant.

Recalling. Oblivion helps and saves. Oblivion guards us mostly from the evil inside of us. It is a good thing, however, that at a certain point, whether we want it or not, we have to recall. And ask ourselves again who and what we are. What unreasonable mistakes we have made with tragic consequences, which we barely survived; and when we stood up for ourselves, at any cost. It is a good thing, I repeat, that we have started recalling.

***

Biography

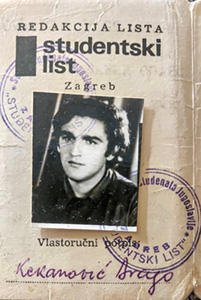

Drago Kekanović (Bratuljevci near Slavonska Požega, 1947). Prose writer, poet, playwright, scriptwriter. Educated in Požega and Osijek. Graduated Comparative Literature and Yugoslav Languages and Literature at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb. Worked as editor in “Studentski list”, “Prolog”, “Polet”, “Prosveta” Serbian Cultural Association publishing. He worked longest as editor and playwright in Television Zagreb, later Radio Television of Croatia. Lives in Zagreb.

***

Books, Awards, Languages

Drago Kekanović published the following books: “Light of Forests”, poems (1965); “Mechanics of the Night, Writings”, stories (1971); “Dinner on the Veranda”, stories (1975); “Ice Forest and other short stories” (1975); “Descendent of Hay”, novel (1978); “Midsummer Night”, novel (1985); “Pannonian Diptych”, two stories (1990); “Fish Path”, novel (1997); “American Ice-cream” (1998); “In the Sky”, stories (2002); “Boar’s Heart”, novel (2012); “Adoption”, stories (2013); “Affection” , novel (2021). He is author of a number of dramas and film scripts.

Winner of “Vladimir Nazor”, “Sava Mrkalj”, “Svetozar Ćorović”, “Vital”, “Borisav Stanković”, “Dušan Vasiljev”, “Branko Ćopić”, “Grigorije Božović”, “Danko Popović”, “Andrić Award”, “Belgrade Victor” awards…

Translated into Polish, English, German, Russian, Spanish, Hungarian, Slovenian…

***

Serbian Writer

I am a Serbian writer with a Zagreb address. That is how I define myself. I am aware of my isolation, and I let my books (damn!) fight for being noticed, I rarely appear in public, I avoid media (at my own detriment, of course) whenever I can. I carried that feeling from Bratulje, that loneliness and solitude are more beneficial than any noise or uproar, that patience is more valuable than gold and that everything will, sooner or later, fall into place.

***

I’m not a Bridge

My experience in it is negligible. And I don’t recommend it to anyone. Heretically or not, even if I weren’t excluded from the constitution of the country I was born in, I would never even think of being a kind of bridge and culturological (please!) connection between nations. Now I see bridges being rebuilt between the two banks, and I’m not on either of them. Good luck to the architects.

***

Dreams of Journeys

I am familiar with your preference for the culture of traveling. I wish that I could join it with my experiences from far away destinations. It is, however, narrow and small, reduced to what has previously been called Mitteleuropa, and took place more in wishes and memories than in reality. Even in my childhood, at the farm in Bratulje, at the pretty isolated former rural landlord’s estate, I traveled to places, which opened up before me after reading my adventure novels, with such passion that I did not feel the need to confirm their existence.